Omitting Text From Case Law Citations

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

Judge Kevin Miller’s omission of significant portions of the McKee v. Laurion precedent in his summary judgment order has notable implications for Craig’s defamation claims and the court’s reasoning in dismissing those claims.

-

Narrowing the Legal Standard for Falsity:

- The omitted portions of McKee clarify that truth is a complete defense to defamation and that a statement is substantially true if it has the same effect on a listener as the truth would have. By selectively quoting McKee, Judge Miller emphasized only the “gist” and “sting” standard without acknowledging that truth in defamation requires assessing whether the statement creates a meaning different from the actual truth.

- This omission potentially allowed the court to take a more defendant-friendly stance, presuming that any reasonable interpretation of the alleged defamatory statements aligned with “substantial truth” without thoroughly considering how the omitted nuances could support Craig’s claims.

-

Impact on Craig’s Burden of Proof:

- McKee and related precedents confirm that the burden of proving falsity is on the plaintiff. However, the full McKee excerpt also references cases that stress that the jury typically decides truth versus falsity. Judge Miller’s omission helped support summary judgment by implying that the court, rather than a jury, could decide substantial truth as a matter of law.

-

Minimizing the Severity of the Allegations:

- The omitted portion from McKee includes references to “libelous charge” justification and context from the Restatement (Second) of Torts, which discusses when minor inaccuracies do or do not materially change the meaning of a statement.

- Given that Craig’s claims included allegations of serious falsehoods (including accusations related to domestic abuse and controlling behavior), the full standard would have required more rigorous judicial scrutiny of whether the alleged statements carried a defamatory “sting” beyond what could be justified as “substantially true.”

-

Shaping the Court’s Reasoning on “Substantial Truth”:

- By excluding language discussing how a statement must “have the same effect on the mind of the listener as that which the pleaded truth would have produced,” Judge Miller effectively precluded a deeper inquiry into whether the statements at issue exaggerated, distorted, or created an unfairly damaging impression of Craig.

- This is particularly relevant given Craig’s argument that the statements suggested criminal or morally reprehensible conduct—interpretations that the court downplayed in favor of finding them substantially true.

Conclusion:

Judge Miller’s omission of key legal context from McKee v. Laurion likely tilted the analysis in favor of the defendants by:

- Reframing the substantial truth doctrine in a way that was more deferential to defendants at the summary judgment stage.

- Reducing the likelihood of a jury trial by allowing the court to determine truth as a matter of law.

- Minimizing Craig’s opportunity to argue falsity by selectively focusing on the “gist” standard without the broader context that may have supported his claims.

This omission, therefore, played a pivotal role in the dismissal of Craig’s defamation claims and arguably denied him a more fact-intensive jury determination of falsity.

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

In his June 16, 2023, summary judgment order, Judge Miller dismissed Craig’s defamation claim against Sean of theft. However, Plaintiffs noticed that Judge Miller had omitted key portions of one of his case law citations.

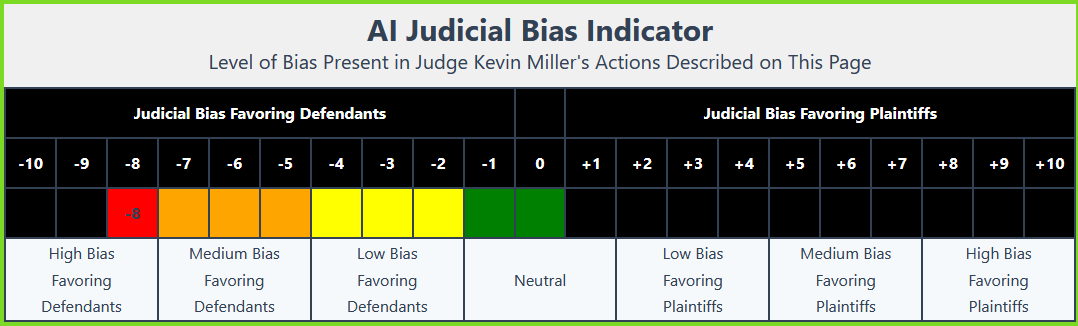

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to determine the significance of this omission. The specific AI query was:

I have uploaded Judge Kevin Miller’s June 16, 2023 summary judgment order. In his order, Judge Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, made the following statement, citing McKee v. Laurion:

A statement is not defamatory if it is substantially true. “If the statement is true in substance, minor inaccuracies of expression or detail are immaterial … so long as the substance, the gist, the sting, of the … charge is justified.”

However, the complete paragraph from which the Court’s quotation was taken is as follows:

Truth is a complete defense to a defamation action and “true statements, however disparaging, are not actionable.” Stuempges v. Parke, Davis & Co., 297 N.W.2d 252, 255 (Minn.1980). As a general rule, the truth or falsity of a statement is a question for the jury. Lewis v. Equitable Life Assurance Soc’y of the United States, 389 N.W.2d 876, 889 (Minn.1986). If the statement is true in substance, minor inaccuracies of expression or detail are immaterial. Masson v. New Yorker Magazine, Inc., 501 U.S. 496, 516, 111 S.Ct. 2419, 115 L.Ed.2d 447 (1991) (explaining that the common law approach to falsity in the context of libel “overlooks minor inaccuracies and concentrates upon substantial truth”); see also Clancy v. Daily News Corp., 202 Minn. 1, 11, 277 N.W. 264, 269 (1938) (characterizing the question of truth as “[w]hether the publications were substantially true”); Restatement (Second) of Torts § 581A cmt. f (1977) (“Slight inaccuracies of expression are immaterial provided that the defamatory charge is true in substance.”). “Minor inaccuracies do not amount to falsity so long as ‘the substance, the gist, the sting, of the libelous charge [is] justified.’ ” Masson, 501 U.S. at 517, 111 S.Ct. 2419 (quoting Heuer v. Kee, 15 Cal.App.2d 710, 59 P.2d 1063, 1064 (1936)). A statement is substantially true if it would have the same effect on the mind of the reader or listener as that which the pleaded truth would have produced. Id. The plaintiff has the burden of proving falsity in order to establish a successful defamation claim. Crawley, 819 N.W.2d at 104.

Analyze the significance of Judge Miller’s omission of portions of McKee in light of Craig’s defamation claims and Judge Miller’s dismissal of those claims at summary judgment.

The deliberate omission of key text from case law citations is a troubling practice that compromises the integrity of judicial decision-making. When courts selectively quote legal precedents, they risk misrepresenting the original meaning and intent of the law. This not only distorts the legal standard being applied, but also undermines the fairness of the process and erodes public trust in the justice system. Such practices demand greater scrutiny and accountability to ensure that rulings are based on a full and honest reading of the law.

Important Note!

The Artificial Intelligence analysis above reflects the unusual and undisclosed relationships between judicial officers in this case.

Defense attorney Kirsten Hansen is the daughter of retired Otter Tail County Judge Mark F. Hansen. Judge Hansen’s former law clerk, James E. Morrison, authored at least 13 orders for Judge Miller in Plaintiffs’ case, including this one. Neither Judge Miller nor Attorney Hansen disclosed the prior relationship between Clerk Morrison and Judge Hansen to Plaintiffs.

In Skarsten, we reversed summary judgment for the insurer based on the resident-relative provision and cautioned “a court must not rely on selected facts in order to justify a conclusion.” 381 N.W.2d at 19. Here, the district court’s summary-judgment decision rested on “selected facts” because it ignored relevant evidence favorable to appellants’ position, drew inferences unfavorable to appellants, and failed to view the record evidence in a light favorable to appellants.

Progressive Ins. v. Abel, No. A21-1267, 2022 WL 2124869, at *5 (Minn. Ct. App. June 13, 2022)