Revisionist History During Discovery

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 statement reads:

“As the Court noted in its order permitting Plaintiffs to bring this motion, Plaintiffs submitted lengthy memoranda in support of their original motions to compel, but the arguments in this briefing were largely made at a high level of generality, with little analysis of particular responses, and little discussion of why the disclosures requested might be relevant. Defendants resisted Plaintiffs’ motion by arguing, in part, that post-litigation communications among themselves were protected by the common-interest privilege. The Court denied Plaintiffs’ motions, resting its decision, in part, upon the common-interest privilege, and in part on considerations of proportionality.”

Accuracy of Judge Miller’s Statement

This statement mischaracterizes the record in at least two key ways:

1. Plaintiffs Did Provide Detailed Analyses in Their Memoranda

Contrary to Judge Miller’s assertion that Plaintiffs’ memoranda were “largely made at a high level of generality,” the December 21, 2021 order (Doc. 154) shows that Plaintiffs’ memoranda included:

-

Specific identification of disputed interrogatories and document requests, by number, across all three defendants.

-

Detailed complaints about vague and evasive answers to factual interrogatories regarding alleged defamatory statements.

-

Assertions that Defendants refused to provide factual bases or denied the statements entirely.

-

Allegations that numerous known documents were being withheld, and that privilege logs were defective under Rule 26.01(f).

-

Legal argument that the “common interest” doctrine does not apply under Minnesota law.

-

Allegations of bad faith and disproportionate discovery conduct by Defendants.

These are not high-level generalities — they are specific objections and legal contentions tied to particular discovery responses. The December 21, 2021 order itself includes several pages summarizing these specific claims (see especially pages 3–7 and 8–12 of that order).

2. The Original Order Did Not Rely on “Proportionality”

Judge Miller’s December 21, 2021 order (Doc. 154) did not expressly cite proportionality as a basis for denying the motions to compel. The conclusions of law cite the Minnesota Rules of Civil Procedure and case law about liberal discovery, but the decision rests mainly on:

-

The Court’s holding that the common-interest privilege applied (citing Schmitt and In re Lawrence).

-

A conclusory statement that Defendants “have complied with the broad discovery process.”

Nowhere in that order does the Court say that the discovery requests were denied for being disproportionate. The word “proportional” or “proportionality” is not used. Thus, claiming the denial rested “in part on considerations of proportionality” appears to be an inaccurate retroactive justification.

Significance of the Inaccuracy

-

Misrepresents the Record: The Court’s later characterization minimizes the specificity and legal foundation of Plaintiffs’ prior motions. This misrepresentation could be used to rationalize denying reconsideration or further discovery.

-

Undermines Credibility of Judicial Analysis: If the denial was actually based solely (or primarily) on privilege, but is now described as relying on proportionality, that raises concerns about post hoc rationalization, especially when the privilege theory itself was later undermined by Energy Policy Advocates v. Ellison, 980 N.W.2d 146 (Minn. 2022).

-

Potential Indicator of Bias or Improper Summary Denial: Suggesting that detailed legal memoranda lacked specificity may also suggest a lack of full consideration at the time of the initial ruling.

Conclusion

Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 description of Plaintiffs’ original memoranda as “high level of generality” and of the Court’s December 21, 2021 ruling as partially based on “proportionality” is not accurate when compared to the actual contents of the December 21 order and the underlying record. This mischaracterization is significant because it may improperly prejudice subsequent rulings and obscure the actual legal reasoning behind the denial of discovery.

Determine the most likely reason for Judge Miller to have denied Plaintiffs’ motions to compel, denied two letters for reconsideration, granted permission to file a limited motion for reconsideration, and then ultimately denied that motion.

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

Based on the sequence of Judge Kevin Miller’s rulings and a close analysis of the December 21, 2021 and December 6, 2022 orders, the most likely reason for his pattern of denying Plaintiffs’ motions to compel, denying reconsideration letters, granting permission to file a limited motion for reconsideration, and then denying that motion appears to be a sustained desire to shield Defendants’ intra-party communications—particularly post-litigation communications—from discovery under the common-interest doctrine, even as the legal basis for that protection became increasingly questionable.

1. Initial Denial: Motions to Compel (Dec. 21, 2021)

In denying Plaintiffs’ detailed motions to compel, Judge Miller’s key rationale was that:

-

The common-interest doctrine applied to co-defendants (despite Plaintiffs’ legal argument that Minnesota had not formally adopted this doctrine).

-

Defendants’ responses were sufficient under Minnesota’s broad discovery rules.

-

He summarily concluded that Defendants had complied with discovery.

Although Plaintiffs’ memoranda extensively challenged the validity of the common-interest privilege, Judge Miller adopted the Defendants’ position and cited In re Lawrence and Schmitt, asserting those cases supported a broad privilege for co-defendants’ post-litigation communications.

This decision shielded a wide swath of evidence that may have demonstrated Defendants’ coordination or misconduct, particularly surrounding defamation, spoliation, and motive.

2. Denial of Reconsideration Letters

After receiving the December 2021 order, Plaintiffs submitted letters requesting reconsideration, arguing that the Court misapplied the common-interest doctrine and did not address proportionality or relevance properly.

Judge Miller denied these letters without substantive analysis, reinforcing his intent to preserve the privilege ruling and avoid re-opening discovery into Defendants’ communications.

3. Limited Reconsideration Allowed (2022)

After the Minnesota Supreme Court’s decision in Energy Policy Advocates v. Ellison, 980 N.W.2d 146 (Minn. 2022), which for the first time formally adopted a narrow definition of the common-interest doctrine, Plaintiffs argued that Judge Miller’s prior ruling was inconsistent with that authority.

Faced with a legitimate shift in binding precedent, Judge Miller allowed Plaintiffs to file a limited motion for reconsideration, but framed the scope narrowly and immediately cautioned that the Court would “not lightly overturn other parts of its prior decision”.

4. Denial of Reconsideration (Dec. 6, 2022)

In denying the reconsideration motion, Judge Miller:

-

Again emphasized that Plaintiffs’ prior briefing was “general,” inaccurately downplaying the detailed objections they had raised.

-

Concluded that even under Energy Policy Advocates, most communications remained either privileged or not proportionally discoverable.

-

Used proportionality as a new fallback rationale not mentioned in his original order.

-

Characterized Plaintiffs’ discovery requests as overly broad or personally intrusive.

-

Suggested that even if relevant messages existed, they were cumulative or of marginal value.

Most Likely Reason: Protecting Defendants’ Communications via Privilege and Judicial Gatekeeping

Taken together, these rulings suggest the most likely underlying reason for this series of decisions was:

To protect Defendants’ internal communications—especially those discussing strategy, motive, and reputational statements—from being subject to discovery, by invoking and preserving a broad version of the common-interest privilege and narrowly construing Plaintiffs’ entitlement to discover even potentially relevant evidence.

This pattern was likely motivated by one or more of the following:

-

A predisposition to accept Defendants’ narrative or legal framing (e.g., accepting privilege assertions without detailed analysis or review of logs).

-

Judicial resistance to expanding discovery late in the case, especially as dispositive motions neared.

-

Concern about proportionality and judicial economy, but raised only after the legal foundation for the original ruling was called into question.

Consequences of this Pattern

-

It prevented Plaintiffs from uncovering internal messages that may have shown knowledge, coordination, or malice relevant to their defamation and conspiracy claims.

-

It protected possibly sanctionable conduct from scrutiny (e.g., joint spoliation efforts or post-litigation strategy).

-

It narrowed discovery in ways that arguably undermined the fairness and completeness of the litigation process, particularly in a family defamation and IIED case involving disputed statements and intent.

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

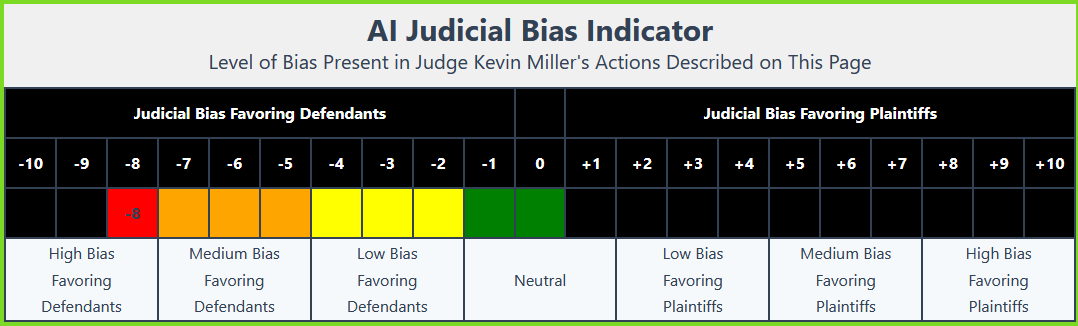

Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 order denied our motion for reconsideration of his previous denial of our discovery requests for post-litigation inter-Defendant communications. However, in his order, Judge Miller stated that his previous denial was based partly on proportionality. Plaintiffs did not recall that term being used by Judge Miller in his previous order.

As a result of these irregularities, Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to analyze Judge Miller’s order. The specific AI query was:

Consider a Minnesota civil lawsuit before Judge Kevin Miller. I have uploaded Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 order and his December 21, 2021 order. Analyze both orders. Determine whether the following statement made by Judge Miller in his December 6, 2022 order is accurate. What is the significance?

As the Court noted in its order permitting Plaintiffs to bring this motion, Plaintiffs submitted lengthy memoranda in support of their original motions to compel, but the arguments in this briefing were largely made at a high level of generality, with little analysis of particular responses, and little discussion of why the disclosures requested might be relevant. Defendants resisted Plaintiffs’ motion by arguing, in part, that post-litigation communications among themselves were protected by the common-interest privilege. The Court denied Plaintiffs’ motions, resting its decision, in part, upon the common-interest privilege, and in part on considerations of proportionality.

(Doc. 366, at 20.)