False Allegation of Theft

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

This passage from Judge Kevin Miller contains several irregularities, both in legal reasoning and logical consistency. Below is an analysis of the key issues:

1. Inconsistent Use of Minnesota Theft Law

- Judge Miller initially states that Craig and Renee’s marriage negates the possibility of theft because Minnesota law (Minn. Stat. § 609.52, subd. 1(8)) precludes theft between spouses.

- However, he then contradicts this by analyzing whether Craig’s actions meet the statutory elements of theft, despite having already concluded that Craig could not legally commit theft against Renee.

- This is an internally inconsistent argument: If marriage negates theft, then any further discussion about whether Craig’s actions met the statutory elements of theft is irrelevant.

2. Judge’s Use of “Setting Aside” Marriage

- The judge twice states that he is “setting aside” the fact that Craig and Renee were married, despite the fact that marriage is a legally dispositive fact regarding theft allegations.

- It is legally improper to “set aside” a fact that is central to the legal analysis. If marriage legally precludes a theft charge, then any further discussion about whether theft occurred is moot.

3. Shifting Standards in Defamation Analysis

- Judge Miller acknowledges that Sean explicitly accused Craig of “stealing” from Renee.

- He then states that, based on context, Sean could not have been accusing Craig of a literal crime.

- However, he later suggests that an ordinary person could reasonably interpret Craig’s actions as theft, which contradicts his earlier statement that Sean’s statement did not constitute an actual accusation of theft.

- If Sean’s statement was merely a subjective interpretation (not a factual claim), then why analyze whether Craig’s actions met the elements of theft at all?

- Conversely, if the court is engaging in a theft analysis, it suggests that Sean’s statement was a factual claim, which undermines the argument that it was purely an opinion.

4. Logical Inconsistencies in Defamation Analysis

- Judge Miller states that Sean’s accusation was substantially true because Craig took money without consent.

- However, he also acknowledges that intent is a key element of theft.

- If intent is uncertain or subject to multiple interpretations, then Sean’s statement—that Craig “stole”—is not a factual assertion but rather a disputed conclusion.

- Under Minnesota defamation law, an outright false statement of fact is defamatory, but opinion based on disclosed facts is not. The issue is whether Sean’s statement presents itself as a factual assertion or opinion.

- The judge’s reasoning conflates these two standards, treating Sean’s statement as both an objective fact (thus requiring legal analysis) and a subjective opinion (thus allegedly immune from defamation claims).

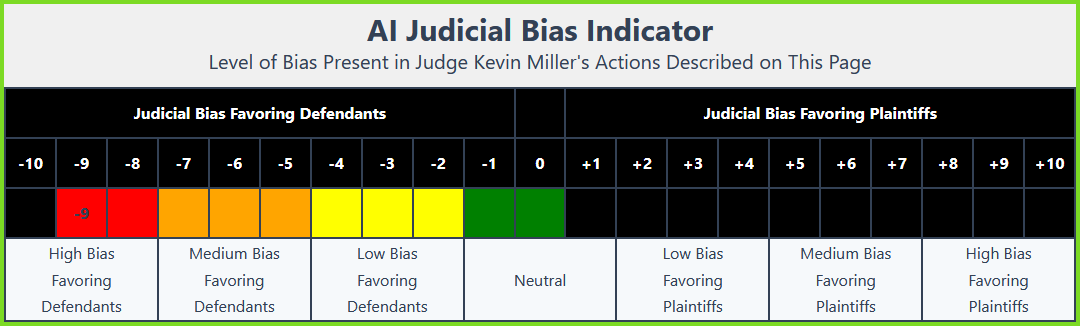

5. Potential Judicial Bias

- The judge’s reasoning appears to go to great lengths to excuse Sean’s defamatory statement.

- He begins by concluding that theft was legally impossible, yet he still provides an alternate framework to justify the statement as true.

- The argument is structured to dismiss the defamation claim rather than to neutrally evaluate the legal principles involved.

Conclusion

Judge Miller’s analysis contains multiple inconsistencies:

- He both applies and disregards the marriage defense at different points.

- He analyzes theft despite initially concluding that theft was impossible.

- He treats Sean’s statement as both a non-accusatory opinion and a legally justified fact, depending on what best supports dismissing the defamation claim.

- He misapplies defamation law by conflating subjective opinion with objective factual claims.

These irregularities suggest that the judge’s reasoning was results-driven rather than legally sound.

In his June 16, 2023 Order Granting Summary Judgment, Judge Kevin Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, granted summary judgment to Defendants. Analyze the order, which contains the following paragraphs related to defamation, for any irregularities and to determine whether summary judgment was properly granted:

[Portion of Judge Miller’s summary judgment order as previously submitted]

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

The order granting summary judgment in favor of Defendants raises several significant irregularities and potential errors in legal reasoning. Below is a detailed analysis of the key issues:

1. Judicial Inconsistency in Treating Craig and Renee’s Marriage

- Judge Miller repeatedly states, “Setting aside the fact that Craig and Renee were married at the time,” which is legally problematic. Under Minnesota law, one spouse cannot commit theft against the other during a marriage because of their shared inchoate interest in property (Minn. Stat. § 609.52, subd. 1(8); State v. Arnold, 235 N.W. 373 (Minn. 1931); State v. Mayhood, 241 N.W.2d 803, 806 (Minn. 1976)).

- Despite acknowledging this, Judge Miller inconsistently ignores it when analyzing whether Sean’s statements were defamatory. If theft was legally impossible due to the marriage, then Sean’s explicit accusation that Craig “stole” would necessarily be false. Yet, the court still concludes that the statement was “substantially true.”

Significance: This contradiction undermines the entire legal basis for granting summary judgment. The judge acknowledges that theft could not have occurred, yet he justifies dismissal of the defamation claim by asserting that Sean’s statement was a “reasonable interpretation” of the facts.

2. Misapplication of the “Substantial Truth” Doctrine

- The court relies on McKee v. Laurion, 825 N.W.2d 725, 730 (Minn. 2013), for the principle that a statement is not defamatory if it is “substantially true.”

- However, applying McKee here is flawed because McKee involved minor inaccuracies that did not change the fundamental meaning of the statement. In contrast, Sean explicitly used the word “stole,” which denotes the crime of theft, and theft was legally impossible under Minnesota law due to Craig and Renee’s marriage.

- The order states: “The gist of Sean’s statement — that Craig took actions that reasonably caused Renee to feel as though Craig had stolen from her — is ultimately accurate.” However, this mischaracterizes the defamation standard. What matters is whether Sean’s statement conveyed an objectively false assertion of fact, not whether it subjectively “felt” like theft to Renee.

- The Minnesota Supreme Court has held that a statement is actionable if it conveys a false and defamatory meaning to a reasonable reader. Jadwin v. Minneapolis Star & Tribune Co., 367 N.W.2d 476, 481 (Minn. 1985). Here, an ordinary person would interpret “stole” to mean criminal theft, not merely a subjective feeling of wrongdoing.

Significance: The court improperly expanded the “substantial truth” doctrine to cover a statement that falsely imputes criminal conduct when no crime occurred.

3. Selective Use of Evidence to Favor Defendants

- The court states: “Craig has admitted to taking Renee’s movable property without her consent.”

- However, the order does not clarify the circumstances under which Craig took the property. If the property was taken as part of a marital separation and Craig believed he had a right to it, then there is no clear evidence that he acted with criminal intent.

- The order also states: “Craig does deny that he intended to permanently deprive Renee of the property in question. But, of course, the fact that he did not return the property until prompted could reasonably support the opposite inference.” This misapplies summary judgment standards, which require courts to view the evidence in the light most favorable to the non-moving party (Plaintiffs). Instead, the court improperly draws inferences against Craig to justify its decision.

Significance: Summary judgment should not be granted when there are factual disputes about intent. The presence of disputed intent should have precluded summary judgment.

4. Mischaracterization of Caselaw to Support Defendants

- The court relies on Hunter v. Hartman, 545 N.W.2d 699, 707 (Minn. App. 1996), stating that “[a] commentator who advocates one of several feasible interpretations of some event is not liable in defamation simply because other interpretations exist.”

- However, Hunter applies to opinions or interpretations of public events. In contrast, Sean’s statement was an unambiguous factual claim that Craig “stole” from Renee. Statements that assert verifiable facts—particularly about criminal activity—are not protected under this doctrine. See Lewis v. Equitable Life Assurance Soc’y, 389 N.W.2d 876, 888 (Minn. 1986) (holding that accusations of criminal conduct are actionable as defamation per se).

Significance: The court misapplied Hunter to a factual assertion, treating an accusation of theft as mere opinion, which is incorrect under defamation law.

5. Erroneous Legal Conclusion That “None of Defendants’ Publications, Taken in Context, Makes the False Allegation of a Crime”

- The court concludes that Sean’s statements were not defamatory per se because they “implied no more than those facts that Craig admits are true.”

- However, Craig did not admit to theft—he denied intent to steal, which is a crucial element of the crime. Thus, Sean’s statement that Craig “stole” remains an objectively false allegation of criminal conduct.

- The Minnesota Supreme Court has recognized that false accusations of crime are defamatory per se. Stuempges v. Parke, Davis & Co., 297 N.W.2d 252, 255 (Minn. 1980). The court’s conclusion directly contradicts this precedent.

Significance: The order improperly dismisses a claim that should have survived summary judgment based on well-established defamation law.

Conclusion

Judge Miller’s ruling contains multiple irregularities and legal errors:

- Contradictory treatment of Craig and Renee’s marriage—acknowledging that theft was legally impossible but still justifying Sean’s accusation.

- Misapplication of the substantial truth doctrine—wrongly treating a false accusation of a crime as an opinion.

- Improper resolution of factual disputes—drawing inferences against Plaintiffs rather than in their favor, as required at summary judgment.

- Selective and misleading use of caselaw—applying cases that protect subjective commentary to an objective, verifiable false statement.

- Failure to properly analyze defamation per se—ignoring Minnesota law that treats false accusations of crime as inherently defamatory.

Given these issues, the grant of summary judgment on Plaintiffs’ defamation claims appears legally unsound. Plaintiffs presented evidence of a false statement that accused Craig of a crime, which is generally considered defamation per se. Since summary judgment is improper where factual disputes exist—especially regarding intent—the case should have proceeded to trial for a jury determination.

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

One of Plaintiff Craig Stevenson’s claims was that Sean had falsely accused him of stealing from Renee. Craig vehemently denied this allegation. However, despite Craig’s denial, Judge Miller dismissed this claim at summary judgment.

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to analyze a portion of Judge Miller’s June 16, 2023 summary judgment order related to this defamation claim against Sean. (Doc. 429, at 22-25.) The specific query was:

Analyze the following quote from Judge Kevin Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, for any irregularities:

Finally, Plaintiffs argue that Sean falsely accused Craig of stealing from Renee. Sean did explicitly use the word “stole,” which denotes the crime of theft. However, it is clear from context that Sean could not be referring to the literal crime of theft. This is because it is clear that the events to which Sean was referring occurred while Craig and Renee were still married. He stated that, during the breakdown of the marriage, Craig had moved money out of the marital home. But theft of movable property requires that the actor take “property of another.” Minn. Stat. § 609.52, subd. 2(a)(1),(5)(i). “Property of another” does not includes [sic] property in which the actor also has an interest if “the actor and the victim are husband and wife.” Minn. Stat. § 609.52, subd. 1(8). As such, Minnesota courts have held that, because both spouses have an inchoate interest in each other’s property during a marriage, one spouse cannot be guilty of stealing from the other. See State v. Arnold, 235 N.W. 373 (Minn. 1931); see also State v. Mayhood, 241 N.W.2d 803, 806 (Minn. 1976) (declining to overrule Arnold). When taken in their full context, Sean’s messages themselves negate an element of the offense of theft. From an objective perspective, then, Sean’s statement contains no actual allegation of a crime.

Setting aside the fact that Craig and Renee were married at the time, Minnesota law provides that an actor is guilty of theft when the actor “intentionally and without claim of right takes, uses, transfers, conceals or retains possession of movable property of another without the other’s consent” if the act is done either (1) “with intent to deprive the owner of possession [permanently]” or (2) “with intent to exercise temporary control” and “the control exercised manifests an indifference to the rights of the owner or the restoration of the property to the owner.” Minn. Stat. § 609.52, subd. 2(a)(1),(5)(i).

Here, Craig has admitted to taking Renee’s moveable property without her consent. That admission establishes all of the above-referenced elements, save for his intent. Craig does deny that he intended to permanently deprive Renee of the property in question. But, of course, the fact that he did not return the property until prompted could reasonably support the opposite inference. Moreover, he clearly intended to exercise at least temporary control of the property. And he displayed the money in question to another person while it was in his control. It is more than arguable that this act manifested an indifference to Renee’s rights to control the property and manifested a purpose beyond simply sorting through the property to divide it properly. Thus, even assuming that Craig’s version of the facts is true, it is a reasonable interpretation of these facts that Craig engaged in what an ordinary person would describe as theft.

A statement is not defamatory if it is substantially true. “If the statement is true in substance, minor inaccuracies of expression or detail are immaterial … so long as the substance, the gist, the sting, of the … charge is justified.” McKee, 825 N.W.2d at 730. Moreover, “[a] commentator who advocates one of several feasible interpretations of some event is not liable in defamation simply because other interpretations exist.” Hunter v. Hartman, 545 N.W.2d 699, 707 (Minn. App. 1996). “Consequently, remarks on a subject lending itself to multiple interpretations cannot be the basis of a successful defamation action because as a matter of law no threshold showing of ‘falsity’ is possible in such circumstances.” Id. “[I]f it is plain that the speaker is expressing a subjective view, an interpretation, a theory, conjecture, or surmise, rather than claiming to be in possession of objectively verifiable facts, the statement is not actionable.” Schlieman v. Gannett Minnesota Broad., Inc., 637 N.W.2d 297, 308 (Minn. App. 2001).

The issue here is fundamentally one of Craig’s intent. Setting aside the fact that Craig and Renee were married at the time — a defense to criminal liability which Sean’s statement itself established — Craig has admitted to facts that would establish the act requirements of theft. And he has also admitted to facts that would allow a reasonable person to infer that he had the requisite criminal intent to establish the offense of theft. Criminal intent is, of course, not something generally subject to direct proof. A person does not generally know what another is thinking, and nothing about Sean’s statement suggests that he is claiming to have special insight into Craig’s thoughts. Rather, criminal intent is generally shown circumstantially. As such, it is clear enough that Sean was drawing an available conclusion about Craig’s intent circumstantially, by offering a reasonable interpretation of the same underlying facts that Craig admits are true. Understood in light of both caselaw and common sense, Sean’s statement implied no more than those facts that Craig admits are true. The gist of Sean’s statement — that Craig took actions that reasonably caused Renee to feel as though Craig had stolen from her — is ultimately accurate. Even if Craig had an innocent intent, Sean’s statement is merely a non-actionable gloss on those undisputed facts.

Because none of Defendants’ publications, taken in context, makes the false allegation of a crime, Plaintiffs’ claims of defamation per se must be dismissed.

The handling of false allegations within the legal system—especially those involving claims of theft in civil disputes—raises serious concerns about fairness, integrity, and due process. When courts dismiss these claims without fully addressing conflicting evidence or the potential harm to reputations, it erodes public trust and leaves individuals without meaningful recourse. The process often appears more focused on expediency than truth, highlighting troubling gaps in accountability and legal protections for the wrongfully accused.

Important Note!

The Artificial Intelligence analysis above reflects the unusual and undisclosed relationships between judicial officers in this case.

Defense attorney Kirsten Hansen is the daughter of retired Otter Tail County Judge Mark F. Hansen. Judge Hansen’s former law clerk, James E. Morrison, authored at least 13 orders for Judge Miller in Plaintiffs’ case, including this one. Neither Judge Miller nor Attorney Hansen disclosed the prior relationship between Clerk Morrison and Judge Hansen to Plaintiffs.

In Skarsten, we reversed summary judgment for the insurer based on the resident-relative provision and cautioned “a court must not rely on selected facts in order to justify a conclusion.” 381 N.W.2d at 19. Here, the district court’s summary-judgment decision rested on “selected facts” because it ignored relevant evidence favorable to appellants’ position, drew inferences unfavorable to appellants, and failed to view the record evidence in a light favorable to appellants.

Progressive Ins. v. Abel, No. A21-1267, 2022 WL 2124869, at *5 (Minn. Ct. App. June 13, 2022)