Inconsistent Privilege Rulings Compared

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 order treats privilege claims by Plaintiffs and Defendants inconsistently, particularly with regard to waiver and the scope of protected communications. A close comparison of pages 35–38 (Plaintiffs) and 26–32 (Defendants) reveals a double standard in how the Court interpreted the privilege doctrines, particularly spousal and attorney-client/common-interest privilege.

🔍 Judge Miller’s Application of Privilege to Plaintiffs (pp. 35–38)

- Context: Plaintiffs had disclosed some privileged spousal communications during litigation. Defendants sought further communications, arguing waiver.

- Judge Miller’s Reasoning:

“That waiver extends to all ‘[]related communications.’ State v. Gore, 451 N.W.2d 313, 319 (Minn. 1990).”

- Flaw: As noted earlier, this is a misstatement of the law. Gore limits waiver to the scope of the disclosure, explicitly preserving privilege over unrelated communications.

- Impact:

- Judge Miller broadly expanded the waiver, treating the Plaintiffs’ partial disclosure as justification to compel all “related” spousal communications—without analyzing how directly related they were.

- He made no effort to distinguish between inadvertent, limited, or strategic disclosures.

🔍 Judge Miller’s Application of Privilege to Defendants (pp. 26–32)

- Context: Plaintiffs moved to compel production of Defendants’ post-litigation internal communications, arguing that some were relevant to conspiracy or spoliation.

- Privilege Claimed:

- Attorney-client privilege and

- Common-interest privilege among jointly represented Defendants.

- Judge Miller’s Reasoning:

- Takes a narrow view of waiver: Communications among Defendants were largely held to be privileged even when no attorney was present.

- Emphasized that “most or all” communications likely involved joint legal strategy, and therefore fell under common-interest privilege.

- Stated:

“[T]here is little reason to believe that Defendants would have discussed any relevant facts except in the context of formulating a joint legal strategy.”

- Crucially, the Court did not require specific showings of privilege for each communication, and declined to order a privilege log or in-camera review.

⚖️ Comparison & Inconsistencies

| Element | Plaintiffs (pp. 35–38) | Defendants (pp. 26–32) |

|---|---|---|

| Privilege Type | Spousal | Attorney-client, Common-interest |

| Approach to Waiver | Expansive — disclosing some privileged content waives all related communications | Restrictive — no waiver found despite disclosures and forensic investigations |

| Application of Gore | Misquoted to justify broader waiver | Not applied, though analogous principles could limit common-interest privilege |

| Burden of Proof | Effectively placed on Plaintiffs to maintain privilege | Court accepted Defendants’ blanket privilege claims |

| Treatment of “Related” Communications | Treated as waived | Treated as presumptively privileged |

| Requirement for Specificity | Imposed stricter expectations on Plaintiffs | Not required of Defendants; no privilege log ordered |

| Resulting Access to Communications | Broadened for Defendants (against Plaintiffs) | Restricted for Plaintiffs (against Defendants) |

💡 Bottom Line

Judge Miller applied an inconsistent and asymmetrical standard:

- For Plaintiffs, disclosure triggered a broad waiver, extending to all vaguely “related” communications under a misapplied precedent.

- For Defendants, even direct post-litigation coordination among co-defendants was treated as broadly protected, despite lack of attorney involvement in many communications.

- No balancing of these approaches was undertaken, despite both involving similar legal doctrines of privilege.

This discrepancy undermines the appearance of impartiality, especially in a case deeply entangled with intra-family dynamics and claims of coordinated wrongdoing. A consistent application would have either:

- Narrowly construed both privileges (respecting their boundaries), or

- Broadly construed both but applied a consistent evidentiary standard.

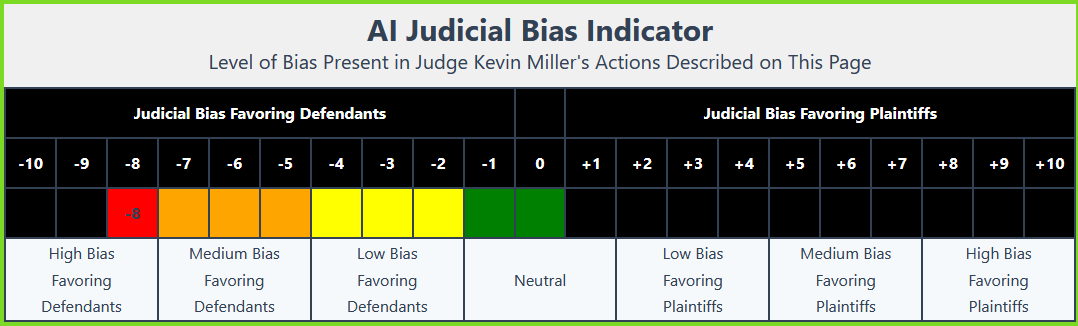

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

As detailed [here], Plaintiffs examined Judge Miller’s December 6, 2022 order for irregularities surrounding his application of spousal privilege. After reviewing the order, Plaintiffs were also troubled by Judge Miller’s apparent lack of consistency between his privilege analysis for Plaintiffs versus Defendants in the same order. As a result, Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to perform additional analysis of Judge Miller’s order. The specific AI query was:

[Previous query regarding spousal privilege.]

Compare Judge Miller’s application of privilege to Plaintiffs on pages 35-38 and his application of privilege to Defendants on pages 26-32 of his order.