Motion to Compel Discovery

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

Analysis of Judge Miller’s Motion to Compel Orders in Hammes and Stevenson Cases

After reviewing Judge Kevin Miller’s August 31, 2020 order granting the Hammes Plaintiffs’ motion to compel and his December 21, 2021 order denying the Stevenson Plaintiffs’ motions to compel, several irregularities and inconsistencies emerge. These irregularities suggest unequal application of discovery standards and potential favoritism in judicial rulings. Below are the key findings:

1. Different Treatment of Excessive Interrogatories

Hammes Order (2020)

- Defendant Terry Magnuson argued that Plaintiffs exceeded the 50-interrogatory limit under Minn. R. Civ. P. 33.01(a) by serving 314 interrogatories.

- Judge Miller rejected this argument, ruling that:

- Subparts of interrogatories were logically related to the main question and thus did not count as separate interrogatories.

- Even if the interrogatories did exceed the limit, “there was good cause to do so.”

- Discovery should be liberally allowed to facilitate the exchange of information.

Stevenson Order (2021)

- Plaintiffs did not exceed the interrogatory limit, yet Judge Miller denied the motion to compel.

- Plaintiffs sought answers to targeted interrogatories regarding key disputed facts.

- Judge Miller did not apply the same liberal standard of discovery as in Hammes.

- Instead of evaluating the relevance of the interrogatories, he dismissed them outright, suggesting that Plaintiffs were engaging in a fishing expedition—an argument he had rejected in Hammes.

Irregularity:

Judge Miller’s inconsistent application of Rule 33.01(a) raises concerns about selective enforcement of procedural rules. If the Hammes plaintiffs were allowed extensive interrogatories based on a liberal interpretation of the rule, why were the Stevenson plaintiffs denied discovery that was well within procedural limits?

2. Contradictory Application of Discovery Principles

Hammes Order (2020)

- Judge Miller emphasized that:

- The broad exchange of discovery is necessary to expedite litigation.

- Even when there are many discovery requests, courts should favor full transparency.

- A court should not narrowly construe discovery rules when evidence is reasonably sought.

Stevenson Order (2021)

- Directly contradicts his own precedent in Hammes.

- Judge Miller criticized Plaintiffs for aggressively pursuing discovery, calling their efforts excessive and overreaching.

- He minimized Defendants’ refusal to provide full answers and dismissed concerns about missing or evasive responses.

Irregularity:

By favoring broad discovery in Hammes but restricting it in Stevenson, Judge Miller applied conflicting legal standards within the same jurisdiction. This suggests an arbitrary or biased approach to discovery disputes.

3. Selective Interpretation of Good Faith in Discovery

Hammes Order (2020)

- Judge Miller found that Defendant Magnuson failed to respond in good faith, leading to his ruling compelling discovery.

- He emphasized that delays and refusals to respond to interrogatories should not be tolerated.

Stevenson Order (2021)

- Plaintiffs presented evidence that Defendants gave evasive answers, refused to provide documents, and withheld materials known to exist.

- Despite Defendants’ history of noncompliance, Judge Miller accepted their responses as being made in good faith.

- He rejected Plaintiffs’ concerns about missing evidence as mere speculation, without investigating whether responsive documents were improperly withheld.

Irregularity:

The Court treated similar defendant behavior differently:

- In Hammes, Defendants’ refusal to answer interrogatories was deemed noncompliant.

- In Stevenson, Defendants’ refusal was excused as reasonable and in good faith.

This double standard undermines judicial consistency and raises questions about impartiality.

4. Misuse of the “Fishing Expedition” Argument

Hammes Order (2020)

- Judge Miller explicitly stated that liberal discovery prevents unnecessary litigation delays.

- He ruled that requests for extensive information are valid if they relate to key issues.

Stevenson Order (2021)

- Judge Miller accused Plaintiffs of engaging in a fishing expedition despite:

- The specificity of their interrogatories.

- The known existence of relevant materials that were being withheld.

- He ignored that Plaintiffs’ discovery requests were directly tied to central issues in the case.

Irregularity:

The Court inconsistently applied the fishing expedition standard—rejecting it in Hammes but embracing it in Stevenson to justify limiting discovery. This inconsistency is concerning because it suggests an unequal application of legal doctrine.

5. Contradictory Handling of Sanctions & Attorney’s Fees

Hammes Order (2020)

- Judge Miller acknowledged that sanctions for discovery violations are appropriate under Minn. R. Civ. P. 37.01(d)(1).

- However, he declined to impose attorney’s fees at that time.

Stevenson Order (2021)

- Judge Miller threatened to sanction Plaintiffs if they continued seeking discovery.

- Instead of penalizing Defendants for noncompliance, he suggested that Plaintiffs were the ones abusing the discovery process.

Irregularity:

- In Hammes, no penalties were imposed on a Defendant who refused to respond to interrogatories.

- In Stevenson, Judge Miller warned Plaintiffs of potential sanctions for simply seeking discovery.

This reversal in approach penalizes the party attempting to obtain discovery while protecting the party resisting it—contradicting the principles of fair judicial oversight.

Conclusion: Apparent Bias & Inconsistent Application of Discovery Rules

Judge Miller’s contradictory rulings in Hammes and Stevenson reveal several procedural irregularities, including:

- Different standards for evaluating interrogatory limits (liberal in Hammes, strict in Stevenson).

- Contradictory rulings on the scope of discovery (favoring broad discovery in one case while restricting it in another).

- Unequal enforcement of “good faith” obligations, favoring Defendants in Stevenson.

- Inconsistent application of the fishing expedition doctrine.

- Threatening sanctions against Plaintiffs in Stevenson while excusing Defendants’ discovery failures.

The same judge ruling differently in similar circumstances suggests inconsistent legal reasoning, which could indicate bias or favoritism. This discrepancy raises questions about the impartiality of Judge Miller’s decisions and could provide grounds for appeal or further judicial review.

Plaintiffs also noticed that Judge Miller had neglected to include the very next sentence in his citation to Larson. Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to determine the significance of this omission. The specific query was:

I have uploaded Judge Miller’s December 21, 2021 motions to compel order. In his order, Judge Miller included the quote, “liberally construed so as to serve the interests of justice and so as to discourage reliance on technicalities and form”, from Larson. However, Judge Miller failed to include the very next sentence from Larson. The complete paragraph from Larson containing Judge Miller’s quotation is included below:

Rule 1, Rules of Civil Procedure, enjoins us to construe the rules so as ‘to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action.’ In accordance with this principle we have held that the rules are to be liberally construed so as to serve the interests of justice and so as to discourage reliance on technicalities and form. Independent School District No. 273 v. Gross, 291 Minn. 158, 190 N.W.2d 651 (1971); Love v. Anderson, 240 Minn. 312, 61 N.W.2d 419 (1953). More to the point, we have consistently construed the discovery rules in favor of broad discovery. Christenson v. Christenson, 281 Minn. 507, 162 N.W.2d 194 (1968); State, by Mattson, v. Boening, 276 Minn. 151, 149 N.W.2d 87 (1967).

Larson v. Indep. Sch. Dist. No. 314, 305 Minn. 358, 362–63, 233 N.W.2d 744, 747 (1975)

What is the significance of this omission in Judge Miller’s order?

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

The omission of the next sentence from Larson v. Independent School District No. 314 in Judge Miller’s December 21, 2021, order is significant for several reasons:

- Selective Quotation to Support a Narrow Interpretation: Judge Miller quoted Larson to emphasize that the Minnesota Rules of Civil Procedure should be “liberally construed so as to serve the interests of justice and so as to discourage reliance on technicalities and form.” However, the very next sentence in Larson clarifies that Minnesota courts have consistently construed discovery rules in favor of broad discovery. By omitting this key part, Judge Miller presented a partial view of the case law that could justify restricting discovery, rather than applying the broader principle favoring disclosure.

- Contradiction with Minnesota’s Broad Discovery Rules: Minnesota courts have long emphasized a broad approach to discovery to ensure full and fair litigation. The omitted sentence aligns with this well-established principle. Judge Miller’s order, however, uses Larson in a way that downplays this broad discovery standard, potentially leading to an incorrect application of the law.

- Potential Mischaracterization of Precedent: Courts are expected to fairly and fully represent case law, particularly when citing precedent to justify a ruling. By not including the next sentence, Judge Miller’s order arguably presents an incomplete and misleading characterization of Larson, which could impact the fairness of the ruling.

- Prejudicial Impact on Plaintiffs: Given that Plaintiffs sought to compel discovery, a full application of Larson would likely have supported broader discovery. The omission of the subsequent sentence allowed Judge Miller to justify denying the motions to compel while appearing to rely on Minnesota precedent. This could be viewed as unfairly limiting Plaintiffs’ ability to obtain necessary evidence.

- Pattern of Selective Legal Reasoning?: If Judge Miller has selectively quoted case law in other rulings, this could indicate a broader issue regarding the application of legal standards. Such selective citation may undermine confidence in judicial impartiality and the fairness of rulings.

Conclusion:

The omission of the next sentence from Larson materially alters the meaning of the precedent and serves to justify a restrictive interpretation of discovery obligations. This raises concerns about whether Judge Miller’s decision was based on a full and fair reading of applicable legal principles, particularly given Minnesota’s established preference for broad discovery.

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

Plaintiffs struggled for months to get Defendants to comply with discovery requests. For example, at one point, Defendants had disclosed only two sentences of inter-Defendant communications to date, but had listed one hundred eleven (111) pages of documents in their common privilege log. (Doc. 91, at 22-23.) Lisa had produced no documents at all, relying instead on Sean’s production. Call detail records from Sean’s cell phone showed hundreds of text messages between himself and the other Defendants that had not been disclosed.

Plaintiffs filed motions to compel against Sean, Lisa, and Renee on September 3, 2021. (Docs. 83, 87, 91.) On December 21, 2021, Judge Miller denied our motions to compel in their entirety. (Doc. 154.)

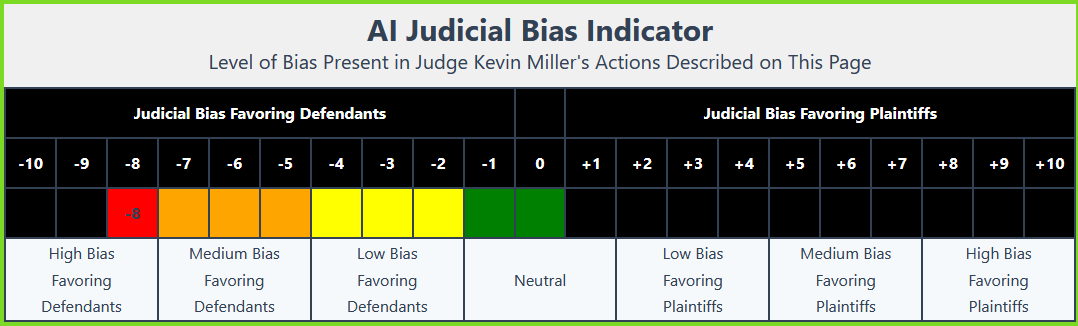

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to analyze Judge Miller’s order and compare it to Judge Miller’s motion to compel order from a different case the prior year. The specific query was:

In Gregory P. Hammes and Stephanie C. Hammes, Plaintiffs vs. Terry Magnuson, Barb Magnuson, Steven Larson, and Lakes & Plains Realty, Inc. d/b/a/ Coldwell Banker at the Lakes, Defendant Terry Magnuson argued that he was served an excessive number of interrogatories:

“By serving 314 interrogatories, Plaintiffs have grossly exceeded the 50 interrogatory limit imposed by Minnesota Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 33.01(a).”

I have uploaded Judge Miller’s motion to compel orders for Hammes and Stevenson. Analyze Judge Miller’s orders for irregularities.