Motion to Extend Discovery

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

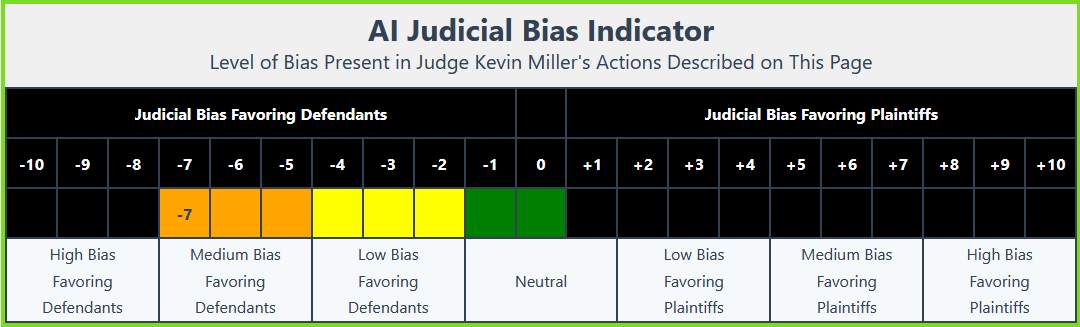

There are several potential irregularities and areas of concern in Judge Kevin Miller’s analysis, particularly in his use of case citations and reasoning regarding the civil conspiracy claim. Below is a breakdown of these concerns:

1. The Citation to Hutchins v. Hutchins (N.Y. 1845)

- The court relies on Hutchins v. Hutchins, a New York case from 1845, to emphasize that actual damages are required for a civil conspiracy claim. However, Hutchins is an exceptionally old case, predating modern American civil conspiracy law.

- Given that civil conspiracy is well-developed in Minnesota case law and other contemporary jurisdictions, citing an 180-year-old New York case as a primary authority is highly unusual.

- More problematic is that Hutchins is a New York case and has little to no precedential value in a Minnesota state court. Generally, when out-of-state case law is used, courts rely on persuasive authority from recent cases or jurisdictions with similar legal frameworks.

- Additionally, while Hutchins does discuss damages as a necessary component, the language and reasoning from an 1845 case do not necessarily align with modern interpretations of civil conspiracy in Minnesota.

2. The Court’s Selective Use of Case Law

- The opinion cites multiple out-of-state cases (Griva, James, Cohen, Bunton, More, Nicolet, Van Royen), but it does not cite any modern Minnesota case law on the issue of damages in a civil conspiracy claim.

- The key Minnesota case the court references, Harding v. Ohio Cas. Ins. Co. (1950), does discuss the requirement of an independent tort for a conspiracy claim. However, the judge fails to acknowledge or analyze any more recent Minnesota case law that might provide clarification.

- By citing cases from Texas, Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and D.C., the judge appears to be building an argument based on out-of-state law rather than Minnesota’s established legal framework.

- This raises a serious question: Why is the court relying on out-of-state cases (some decades old) and an obscure 19th-century New York case rather than Minnesota authority?

3. The Internal Logic of the Argument

- The court suggests that Plaintiffs’ additional discovery requests relate only to the existence of a conspiracy and not to the required element of actual damages.

- However, discovery is precisely the stage where Plaintiffs would seek to uncover evidence of both a conspiracy and resulting damages.

- The judge’s reasoning is circular: He denies discovery on the basis that damages must be shown, but discovery is often needed to establish proof of damages.

- This approach is inherently unfair if Plaintiffs have not yet had a full opportunity to explore damages through discovery.

4. Mischaracterization of Civil Conspiracy Doctrine

- While it is true that civil conspiracy is not an independent cause of action (requiring an underlying tort), the judge’s framing of the issue is questionable.

- The way the judge emphasizes actual damages, combined with the refusal to allow discovery, suggests an attempt to preemptively dismiss the claim before Plaintiffs can properly develop their case.

- Courts generally permit discovery when there is a reasonable basis for believing that relevant information exists, particularly in claims requiring proof of an agreement among defendants.

- By stating there has already been “extensive and burdensome discovery” on this subject, the judge implicitly assumes that further discovery would be fruitless—an assumption that is not clearly supported.

5. The Judge’s Tone and Bias Concerns

- The language used—“virtually all of the additional discovery Plaintiffs seek relates exclusively to their civil conspiracy claims”—suggests an attempt to minimize the relevance of the discovery requests.

- The phrase “extensive and burdensome discovery” further implies that the Plaintiffs have already had more than enough discovery—yet the judge provides no quantification of how much discovery has occurred on damages.

- The emphasis on Hutchins v. Hutchins and other selective citations seems to reflect an attempt to limit Plaintiffs’ claims through procedural restrictions rather than substantive legal reasoning.

Conclusion: Irregularities and Red Flags

- Citing an 1845 New York case is highly unusual and likely inappropriate, given the availability of modern Minnesota authority.

- The judge appears to selectively rely on out-of-state case law while ignoring relevant modern Minnesota precedent.

- The denial of discovery on the basis that damages must be proven is illogical—discovery is the stage where damages would typically be explored.

- The framing of the argument and tone suggests an attempt to dismiss the claim procedurally rather than engaging with the substance of Plaintiffs’ allegations.

- Overall, the analysis in this portion of the order raises serious concerns about judicial impartiality and procedural fairness.

Background and Original AI Query - Click to View

On October 10, 2022, Plaintiffs filed a motion to extend discovery. (Doc. 316.) Plaintiffs filed this motion because just two days prior, Sean Stevenson had testified in a second deposition regarding the extent of his deletion of text messages and his previous false testimony during his first deposition. The results of forensic examinations of Lisa’s and Renee’s phones had also been received on September 29, 2022, and the results of the forensic examinations contradicted Lisa’s recent answer to interrogatories and Renee’s deposition testimony.

On December 6, 2022, Judge Miller denied our motion.

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to analyze Judge Miller’s order with regard to this issue. The specific query was:

In its December 6, 2022 Order and Memorandum Granting in Part, Denying in Part, and Reserving in Part Six Pre-Trial Motions, the Court stated in part:

The Court finds it difficult to conclude, at this juncture, that there is good cause to extend discovery. Virtually all of the additional discovery Plaintiffs seek relates exclusively to their civil conspiracy claims, and exclusively to the element of that claim that requires the existence of a conspiracy. But there has already been extensive and burdensome discovery on this subject. And the existence of a conspiracy is not the only necessary element of these claims. As previously discussed, the claim also requires an independent “tort working damage to the plaintiff.” Harding [v. Ohio Cas. Ins. Co. of Hamilton, Ohio], 41 N.W.2d at 824 [(Minn. 1950)]. Damage means actual damages. Hutchins v. Hutchins, 7 Hill 104 (N.Y. 1845) (“A simple conspiracy, however atrocious, unless it resulted in actual damage to the party, never was the subject of a civil action….” (emphasis added)); see Griva v. Davison, 637 A.2d 830, 849 (D.C. 1994); James v. Bob Ross Buick, Inc., 855 N.E.2d 119, 125 (Ohio App. 2006); Cohen v. Pelagatti, 528 A.2d 657, 659 (Pa. Super. 1987); see also Bunton v. Bentley, 176 S.W.3d 1, 15-16 (Tex. App. 1999); More v. Johnson, 568 P.2d 437, 440 (Colo. 1977); Nicolet, Inc. v. Nutt, 525 A.2d 146, 150 (Del. 1987); Van Royen v. Lacey, 277 A.2d 13, 14 (Md. 1971).

Analyze the preceding quote from Judge Kevin Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, for any irregularities. Also, specifically analyze the citation to Hutchins, a New York case from 1845.