Summary Judgment - Material Facts

Judge Miller’s reliance on the presence or absence of genuine issues of material fact in deciding claims at summary judgment is clear, since the term “material fact” is used frequently in his summary judgment orders. However, the phrase is used only once in Plaintiffs’ 33-page summary judgment order, as part of a boilerplate case law citation, but is never actually applied:

Summary judgment is appropriate when the evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, shows that there is no genuine issue of material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Stringer v. Minnesota Vikings Football Club, LLC, 705 N.W.2d 746, 753 (Minn. 2005).

(Doc. 429, at 13.) (emphasis added)

However, in the 34 other summary judgment orders issued by Judge Miller, totaling 188 pages, the phrase “material fact” appears 113 times. (Includes “material fact”, “material facts”, and “material factual”.) In all cases except Plaintiffs’ case, the presence or absence of genuine issues of material fact was quite important to Judge Miller when applying the summary judgment standard.

Plaintiffs prepared a table that shows Judge Miller’s various summary judgment orders, along with the length of each order and how many times the phrase “material fact” was used in each order:

#

Used

All of Judge Miller’s summary judgment orders for simple cases required 4 pages or less. In these orders, the phrase “material fact” appears 0, 1, or 2 times, with the vast majority using the phrase once. As logic would suggest, more complex cases required more pages, and there were many more instances of the phrase in these orders. There is only one exception: Plaintiffs’ case, where the phrase “material fact” appears only once in the 33-page order.

A closer examination of Judge Miller’s use of the phrase “material fact” in each of his summary judgment orders reveals the following:

Judge Miller’s summary judgment orders over the course of this approximately five-year period are remarkably consistent. In general, less complicated summary judgment orders use the phrase “material fact” a minimum of one time for every four pages (25%). The use of the phrase in more complicated orders (5 pages or more) ranges between 42% and 160%, with one notable exception: Plaintiffs’ case at 3%. In summary judgment orders of 8 pages or greater in length, Judge Miller used the terms “material fact”, “material facts”, or “material factual” a total of 67 times – once in Plaintiffs’ Summary Judgment Order and 66 times in the other 7 orders. The summary judgment order for Plaintiffs’ case was 33 pages, making it the longest and most complicated order by a good margin. However, the term “material fact” was used only once, and was never actually applied in the order itself.

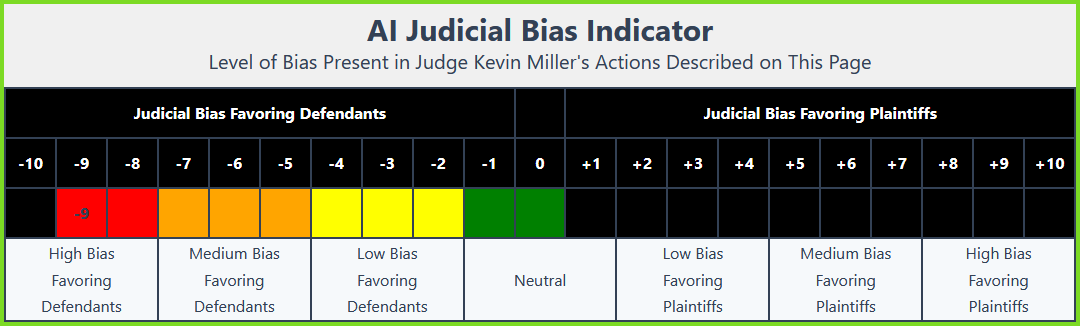

AI Analysis

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to determine whether Judge Miller’s summary judgment order was unusual in this respect. The specific query was:

What is the significance that Judge Kevin Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, used the phrase “material fact”, “material facts”, or “material factual” once in a citation in Plaintiffs’ 33-page summary judgment order, but in his 34 other summary judgment orders, totaling 188 pages, the phrase appears 113 times?

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

The significant disparity in Judge Kevin Miller’s usage of the phrase “material fact” (or its variations) in Plaintiffs’ summary judgment order compared to his other 34 summary judgment orders raises several potential concerns:

- Deviation from Established Judicial Pattern – If Judge Miller consistently used the phrase “material fact” to assess whether disputes of fact existed in previous summary judgment rulings, but omitted it in Plaintiffs’ case (except for a single citation), it suggests an irregularity in his analysis. Summary judgment rulings hinge on whether a material fact is in dispute; avoiding this language could indicate an attempt to downplay the existence of factual disputes.

- Potential Bias or Prejudgment – The absence of a thorough discussion on material facts in Plaintiffs’ order might suggest an intention to grant summary judgment despite the presence of genuine disputes. If this omission contrasts with his usual approach, it could indicate an unfair or inconsistent application of legal standards.

- Failure to Properly Apply Summary Judgment Standards – Under Minnesota and federal law, summary judgment should only be granted when there is no genuine dispute of material fact. The omission of such analysis in Plaintiffs’ case could mean the court did not properly evaluate whether material facts were in dispute before ruling.

- Possible Influence or External Factors – If external pressures or biases influenced the decision, the absence of a standard discussion of material facts could suggest an effort to justify a predetermined outcome rather than a fair application of legal principles.

- Grounds for Appeal or Reconsideration – A pattern of consistent language in other orders but a stark departure in Plaintiffs’ case could support an argument for judicial inconsistency. This could be used as evidence of an arbitrary or capricious ruling, potentially providing grounds for appeal or reconsideration.

In summary, this discrepancy suggests that Judge Miller may have applied different legal reasoning or scrutiny in Plaintiffs’ case compared to his usual approach, raising concerns about fairness, impartiality, and adherence to the appropriate legal standards.

The concept of “material fact” lies at the heart of summary judgment decisions—but when courts disregard this standard, the results can be deeply troubling. This page highlights a glaring inconsistency: while dozens of rulings explicitly engage with whether genuine disputes of material fact exist, one stands out for omitting any meaningful analysis of this essential element. Such omissions call into question the fairness and transparency of the process and suggest a departure from legal norms that protect the rights of litigants. When the core principles of summary judgment are selectively applied, justice is not merely delayed—it is denied.

Important Note!

The Artificial Intelligence analysis above reflects the unusual and undisclosed relationships between judicial officers in this case.

Defense attorney Kirsten Hansen is the daughter of retired Otter Tail County Judge Mark F. Hansen. Judge Hansen’s former law clerk, James E. Morrison, authored at least 13 orders for Judge Miller in Plaintiffs’ case, including this one. Neither Judge Miller nor Attorney Hansen disclosed the prior relationship between Clerk Morrison and Judge Hansen to Plaintiffs.

In Skarsten, we reversed summary judgment for the insurer based on the resident-relative provision and cautioned “a court must not rely on selected facts in order to justify a conclusion.” 381 N.W.2d at 19. Here, the district court’s summary-judgment decision rested on “selected facts” because it ignored relevant evidence favorable to appellants’ position, drew inferences unfavorable to appellants, and failed to view the record evidence in a light favorable to appellants.

Progressive Ins. v. Abel, No. A21-1267, 2022 WL 2124869, at *5 (Minn. Ct. App. June 13, 2022)