The Summary Judgment Standard

In his June 16, 2023 Order Granting Summary Judgment, Judge Miller cited to the following case law regarding summary judgment:

Summary judgment is appropriate when the evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, shows that there is no genuine issue of material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Stringer v. Minnesota Vikings Football Club, LLC, 705 N.W.2d 746, 753 (Minn. 2005). “The district court’s function on a motion for summary judgment is not to decide issues of fact, but solely to determine whether genuine factual issues exist. DLH, Inc. v. Russ, 566 N.W.2d 60, 70 (Minn. 1997).

(Doc. 429, at 13.) (emphasis added)

However, Judge Miller viewed the evidence in the light most favorable to the moving party, in this instance, Defendants, decided many issues of fact, and ignored that the record was filled with disputed factual issues surrounding each claim.

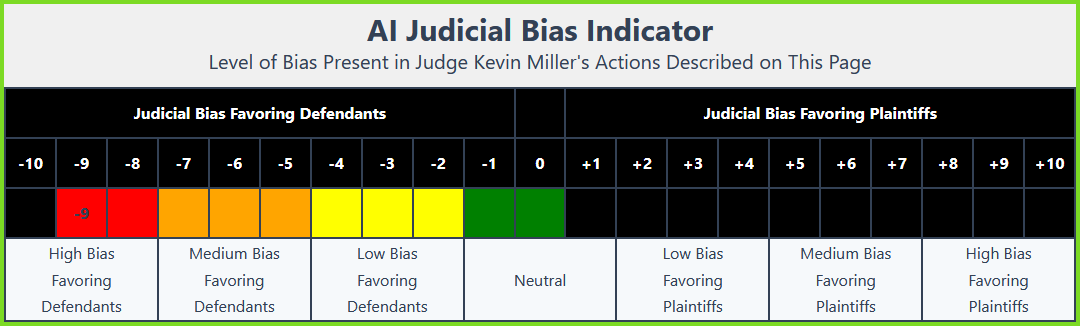

Plaintiffs used Artificial Intelligence to determine whether Judge Miller’s actions were significant. The specific query was:

What is the significance when Judge Miller, a Minnesota district court judge, viewed the evidence in the light most favorable to the moving party, in this instance, Defendants, decided many issues of fact, ignored that the record was filled with disputed factual issues surrounding each claim, and then granted summary judgment?

ChatGPT (AI) Analysis

When a judge, such as Judge Miller, views evidence in the light most favorable to the moving party (Defendants in this case) rather than the non-moving party (Plaintiffs), it represents a significant departure from the proper legal standard for summary judgment. Under Minnesota law, as well as federal law, summary judgment is only appropriate when there are no genuine disputes of material fact and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law (Minn. R. Civ. P. 56.03; DLH, Inc. v. Russ, 566 N.W.2d 60, 69 (Minn. 1997)).

The significance of Judge Miller’s approach includes the following key concerns:

1. Misapplication of the Summary Judgment Standard

- The proper legal standard requires that courts view evidence in the light most favorable to the non-moving party (Plaintiffs in this case). This principle ensures that summary judgment is granted only when no reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party.

- By viewing evidence in favor of the Defendants, Judge Miller effectively tilted the scales of justice, improperly resolving factual disputes that should have been left to a jury.

2. Impermissible Fact-Finding at Summary Judgment

- A judge at the summary judgment stage is not permitted to weigh evidence, assess credibility, or resolve factual disputes (Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 255 (1986)).

- If Judge Miller decided disputed issues of fact in favor of Defendants rather than recognizing them as genuine disputes requiring a trial, this suggests a fundamental error in applying the law.

3. Ignoring the Record of Disputed Issues

- If the record was filled with genuine factual disputes, the case should have proceeded to trial rather than being dismissed at summary judgment.

- Courts must allow factfinders (i.e., juries) to determine disputed issues, rather than resolving them in favor of one party at the pre-trial stage.

4. Potential Judicial Bias or Irregularities

- If a judge consistently misapplies the law in favor of one party, it raises questions about judicial impartiality.

- The pattern of decisions—ignoring clear factual disputes and favoring Defendants—could suggest systemic irregularities or bias.

5. Reversible Error on Appeal

- If properly challenged, such a ruling could be reversed on appeal because it conflicts with well-established precedent governing summary judgment.

- Appellate courts routinely overturn summary judgment decisions where a judge has improperly resolved factual disputes rather than allowing a jury to decide (Fabio v. Bellomo, 504 N.W.2d 758, 761 (Minn. 1993)).

Conclusion

Judge Miller’s approach—favoring Defendants at summary judgment, deciding factual disputes, and disregarding evidence of genuine issues—represents a serious legal error. It undermines the core principle that disputed factual matters must be decided by a jury, not a judge at summary judgment. If this pattern is repeated across multiple cases, it may indicate a broader issue of judicial misconduct or bias, warranting further scrutiny.

As a result of these discrepancies, Plaintiffs reviewed Judge Miller’s summary judgment orders in civil cases from June 1, 2018 through December 31, 2023 using Minnesota Court Records Online (MCRO) to determine how Judge Miller treated other parties at summary judgment. Plaintiffs found a total of 35 civil cases during this period where claims were decided by Judge Miller at summary judgment:

#

#

Summary judgment orders for 33 cases were filed prior to Plaintiffs’ case (bolded above) and a summary judgment order for one case was filed after Plaintiffs’ case. These cases vary widely in their complexity, from simple consumer credit contracts to complicated cases involving shareholder fiduciary responsibilities and real estate disputes. However, in every single case other than Plaintiffs’, Judge Miller appears to have correctly applied the summary judgment standard, as outlined in Stringer and DLH, by granting or denying summary judgment based on the presence or absence of disputed material facts.

Judge Miller deviated from his typical practice in only one out of these thirty-five cases: Plaintiffs’:

The application of summary judgment in legal proceedings is intended to expedite cases by resolving claims where no genuine disputes of material fact exist. However, when courts misapply this standard—by improperly weighing evidence, assessing credibility, or resolving factual disputes without a full trial—it undermines the fundamental right to a fair hearing. Such practices not only tilt the scales of justice but also erode public confidence in the judicial system’s impartiality and integrity. This article critically examines instances where the summary judgment standard has been misapplied, highlighting the detrimental impact on litigants and the broader legal framework.

Important Note!

The Artificial Intelligence analysis above reflects the unusual and undisclosed relationships between judicial officers in this case.

Defense attorney Kirsten Hansen is the daughter of retired Otter Tail County Judge Mark F. Hansen. Judge Hansen’s former law clerk, James E. Morrison, authored at least 13 orders for Judge Miller in Plaintiffs’ case, including this one. Neither Judge Miller nor Attorney Hansen disclosed the prior relationship between Clerk Morrison and Judge Hansen to Plaintiffs.

In Skarsten, we reversed summary judgment for the insurer based on the resident-relative provision and cautioned “a court must not rely on selected facts in order to justify a conclusion.” 381 N.W.2d at 19. Here, the district court’s summary-judgment decision rested on “selected facts” because it ignored relevant evidence favorable to appellants’ position, drew inferences unfavorable to appellants, and failed to view the record evidence in a light favorable to appellants.

Progressive Ins. v. Abel, No. A21-1267, 2022 WL 2124869, at *5 (Minn. Ct. App. June 13, 2022)